In October 2020, Natalie and I presented at Bank Street’s Language Series. The theme that year was Anti-Racist Language Teaching. Our workshop, “Taking an Anti-Racist Stance as a Teacher-Researcher” focused on the question: What stories need to be told in the community where I teach and how will I center them?

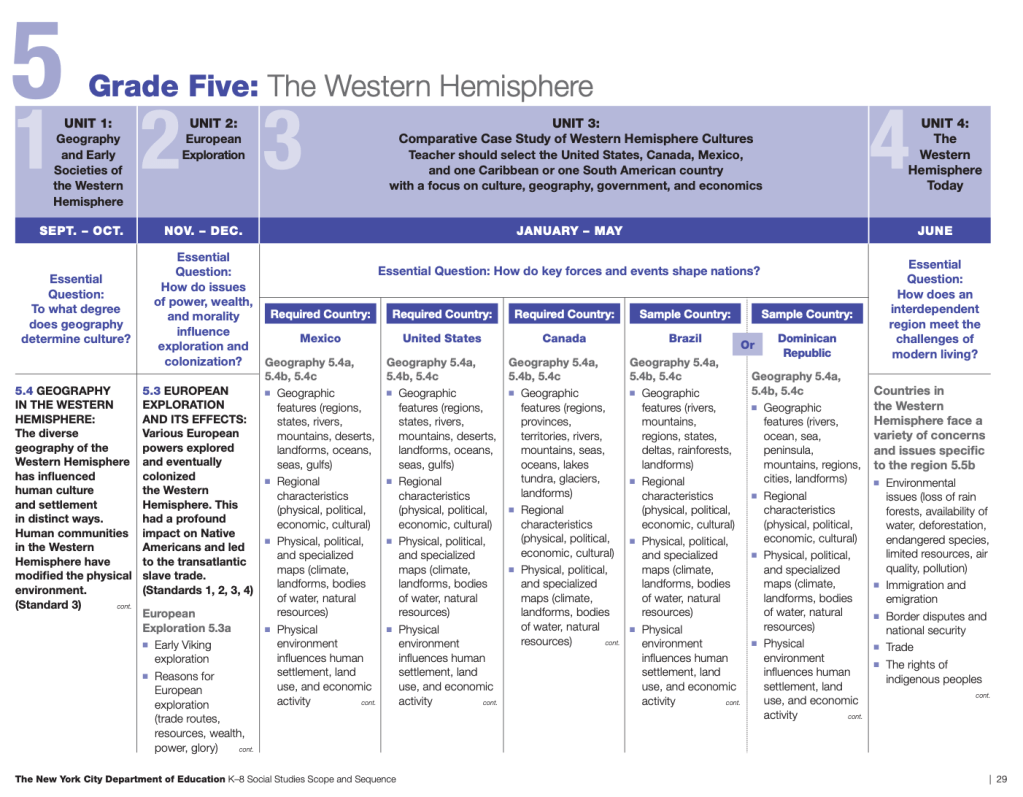

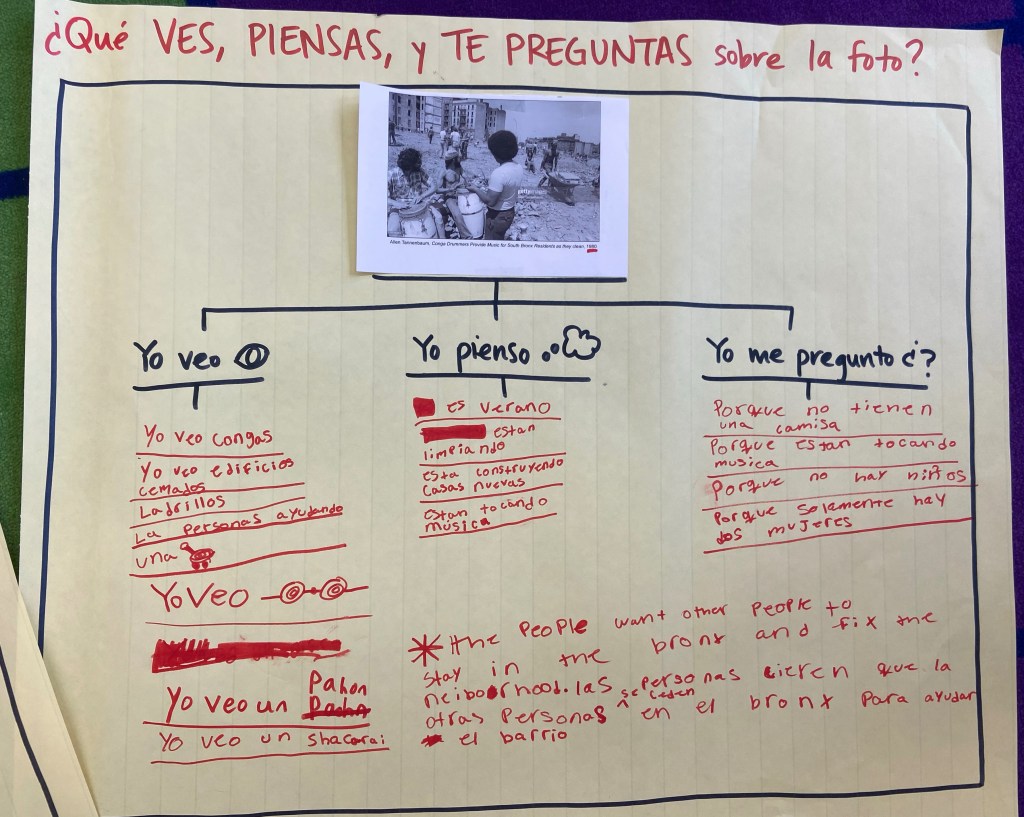

Natalie and I are both white teachers who, at the time, were teaching dual-language in The Bronx (Natalie still does). In our workshop, we got vulnerable and spoke about our status as outsiders to that community — Natalie is from Ohio, and I grew up in Manhattan, which may as well be worlds away from The Bronx. We discussed the strategies that helped us get informed, with the aim of doing soul-affirming, language-rich, student-centered social studies. Learning the history of the South Bronx changed our vision of the neighborhood, correcting our deficit/racist views. We crafted a unit that privileged community voices, shrinking our presence and promoting the agency of students. Our goal with the workshop was to provide participants with tools to start similar journeys. My goal with this post is to give my readers those tools as well.

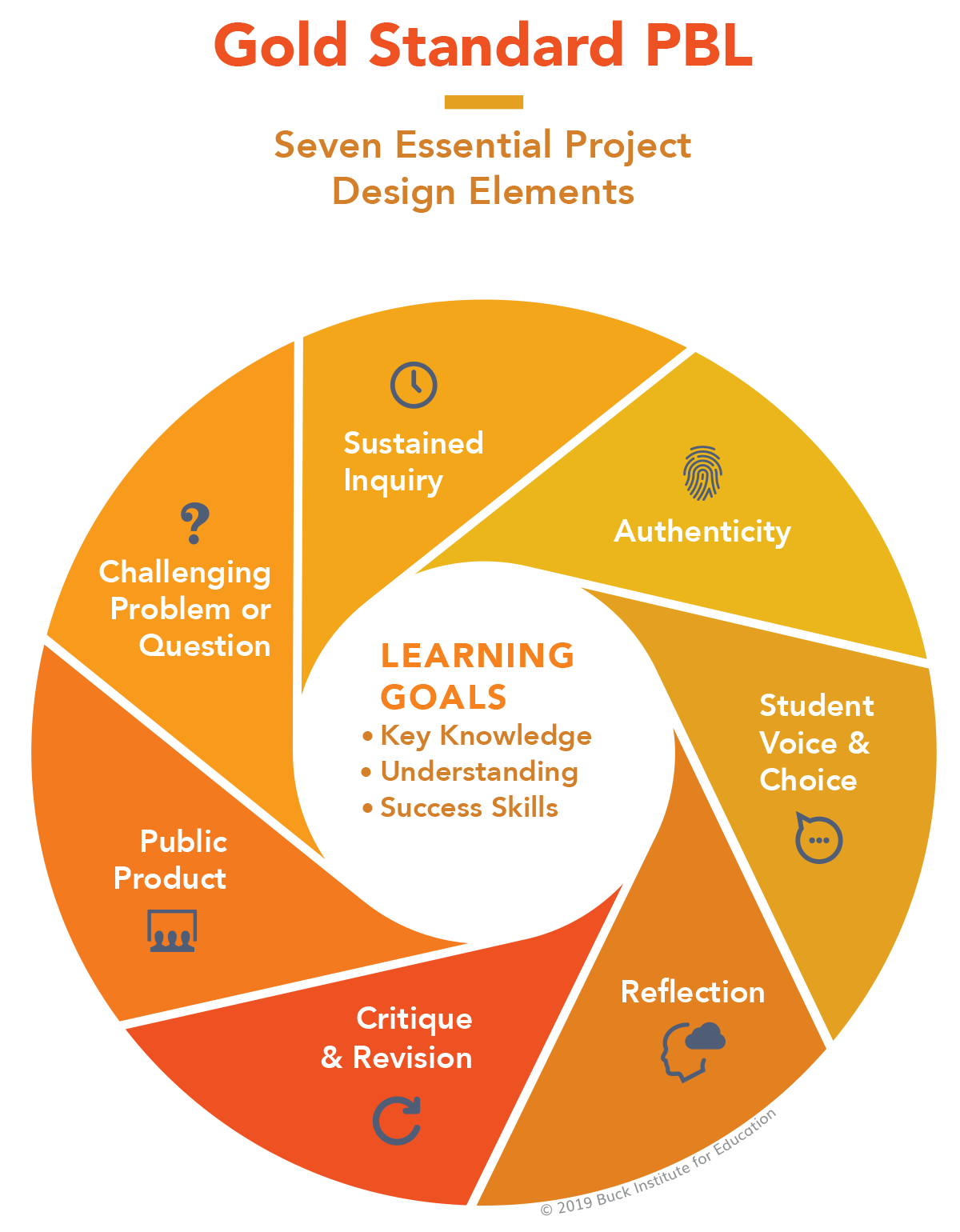

The Importance of Teacher-Research for PBL

I believe that becoming a teacher-researcher and building your own expertise, particularly if you are an outsider to a community (and even if you have been living in the community your whole life!), is essential not just for anti-racist teaching, but also for PBL. In order for projects to take on a life of their own through student interest and “unexpected detours,” as my coworker Lizzie calls them, teachers need to be knowledgeable about the content and flexible enough to facilitate this learning, no matter the direction the detour may take. This doesn’t mean you need to be an expert or prepared for 100 different scenarios, but it does mean you should have a good amount of knowledge under your belt to feel comfortable answering student questions and guiding them towards next steps.

For me, moving to Miami meant I was, yet again, an outsider. For this unit, I knew I wanted to teach about South Florida’s ecosystems, but I needed to learn about them first. I had a lot of questions: What’s a mangrove? Why is the Everglades so special? Isn’t it just flat swampland? Is Miami doomed to be underwater in the next few years?

I got to work.

Research Strategies for Getting Informed

A successful research project uses multiple sources and multiple types of sources. Here are some that are my go-to’s for teacher-research:

- Books

- Photo trove (many libraries and museums have digital collections; you can also find specific photographers’ projects or exhibitions on artists’ or museums’ websites)

- Podcasts

- Talks at local universities

- Museums

- Interviews with community members

- Newspaper and magazine archives

- Community and nonprofit organizations

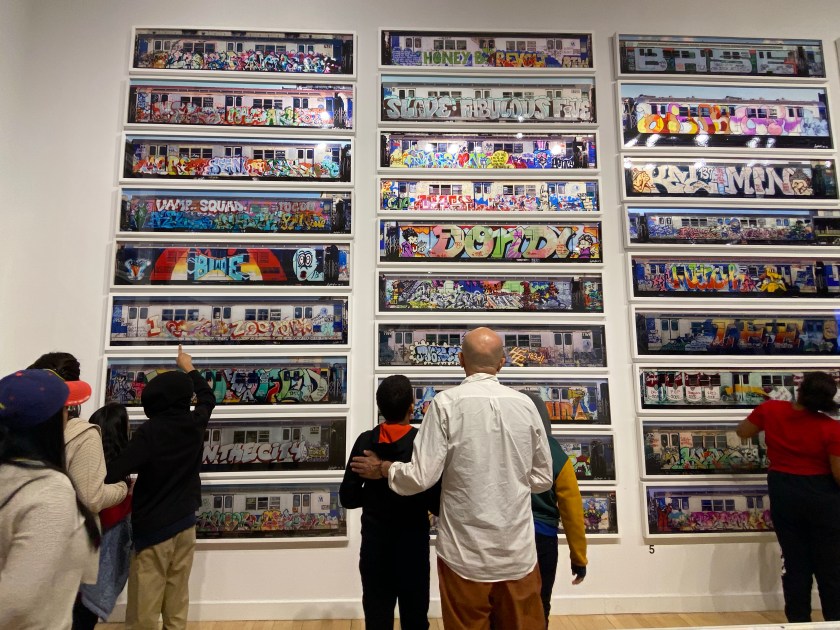

For our Bronx community project, I pored over photographs from the NY Public Library Digital Collections of our school neighborhood in the 40s, 60s, and 70s, finding intersections that we’d be able to place on the map and juxtapose next to photos of what stood there today. I geeked out over a three-part episode from The Bowery Boys about the history of the South Bronx. The Bronx Museum of the Arts had an exhibit with Henry Chalfant’s photographs of the graffitied trains from the 70s and 80s, so we booked a field trip. Natalie, Bryan, and I attended a talk at MCNY to learn about the Young Lords.

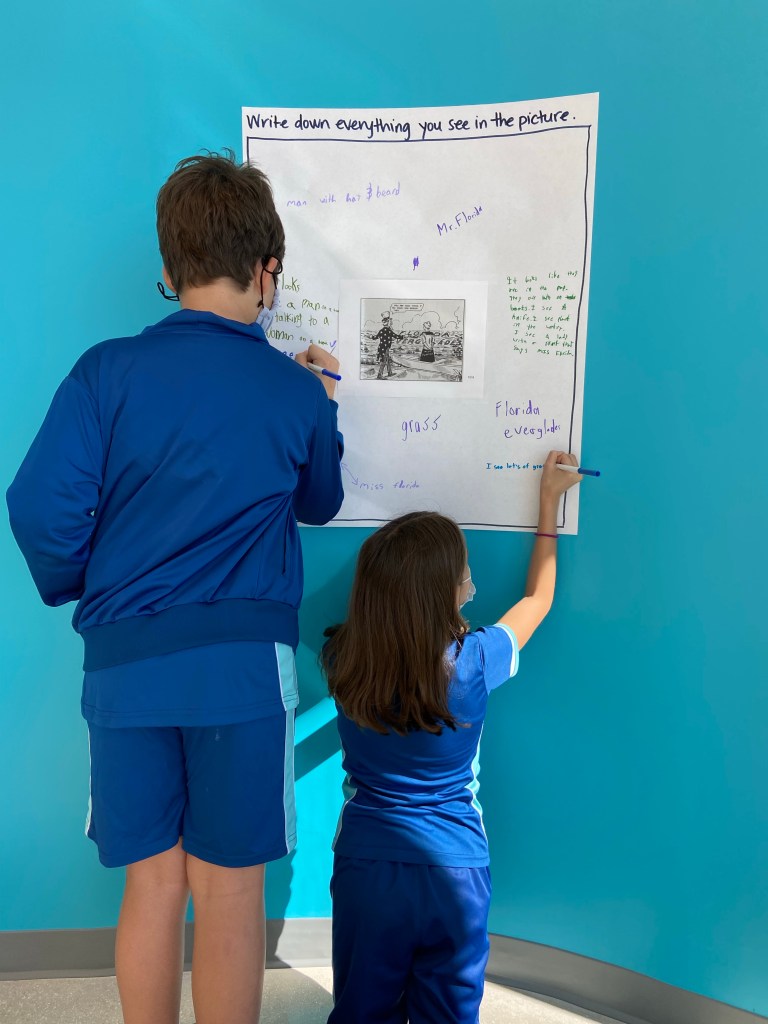

Here in Miami, I ordered a few books to learn more about the history of the Everglades: River of Grass by Marjory Stoneman Douglas and The Swamp by Michael Grunwald, as well as a bunch of picture books for interactive read aloud. I found blogs with old political cartoons and photos, some of which I used for our first provocations. I followed community and nonprofit organizations on Instagram and reached out to some of them for interviews and field trips. I also talked a lot with my coworkers who grew up in South Florida (shout out to Estelle and Josue).

The Beauty of Place-Based Learning: Discoveries for Both Insiders and Outsiders

I think one of my favorite aspects of place-based PBL is that both insiders, who’ve lived in the community forever, and outsiders, who’ve either recently moved there or just commute there from another neighborhood, end up learning so much about their community.

We learned about the resilience and strength of the mangrove forests, and how the Everglades has so many different ecosystems within it. We literally got our hands dirty in order to see this for ourselves.

At the crossroads of Brickell, Little Havana, and The Roads, our school sits alongside I-95, where Xavier Cortada and his 800+ volunteers painted the Miami Mangrove Forest, which we all see every day as we come to work, but never knew the story behind.

We built relationships with organizations that are fighting for the survival of Miami’s ecosystem well into the future, for the benefit of plants, animals, and humans who call Miami home.

Every day that I live and teach here, I grow a deeper appreciation for this city. Through this project, I have gained more faith than before that it will continue to thrive. Watching the fifth graders present to the younger students about mangroves and why we should care about them showed me that they have too.