“Are you going to do the Slice of Life Challenge this year?” Ana asked me this morning as we passed each other in the halls. “Male and Angie are gonna do it, and Gi too.”

“I don’t know…” I skirted. This year’s intention to slice every Tuesday started out strong and then waned in the fall as I dealt with some personal health issues. If I couldn’t commit to doing it weekly, how could I do it daily?

*

Later, when we met in my room, she mentioned it again.

“I just sent an email to the second grade team. Darlyn is in!”

“Maybe…” I smiled. We returned to the writing plans. I shared something funny a student had said about me moving the teacher’s desk.

“That’s a slice!” Ana exclaimed.

“Should I just write it and schedule it for March 1st?”

“YES!”

*

At 3pm, while I was waiting to meet with Male, Ale left Ana’s office and Ana shouted, “Ale’s gonna slice, too!”

“Okay, okay,” I laughed. With this many new slicers from our little school community, surely I could get motivated enough to slice again each day for the month of March. It was tough last year, but it was also fun and satisfying, connecting me not only with other slicers but with friends and family (hi, Mom!). Plus, I have a little time capsule now that captured a joyous month in my life when, among other things, I was falling in love.

So, here it is. Today’s slice. Never mind that it’s a Friday:

*

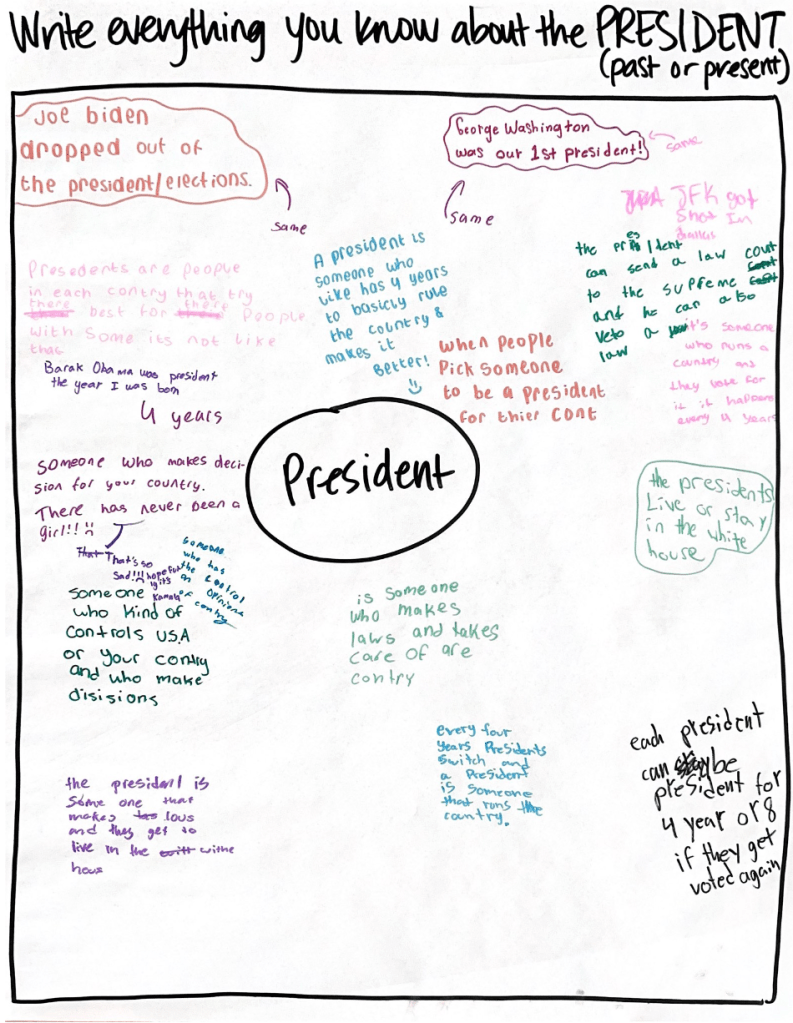

This morning when I entered the classroom at 7:48am, I had visions of the documentation that would start to emerge on the bookshelves as I cleared them. But something wasn’t right. The table by the window always got in the way, and the chairs were all different sizes. There was all this dead space near the teacher table, too, and the math materials were blocked off and inaccessible to the students.

So, I did what I always do when I realize the layout of the classroom doesn’t align with how we’re using it — I started rearranging.

First order of business: moving some of the writing charts. Next? Swapping the teacher table with the long one at the window.

The first students arrived at 8 to find me and all of our tables and chairs scattered.

“Good morning!” I shouted.

“Um, hi? What’s going on?” Two of the girls asked.

“I’m rearranging the furniture. Help me!”

“Okay!” They agreed. These two are always up to help with anything.

“Is this table going to stay on the rug?” The other girl asked, skeptical.

“No, no,” I assured her. “It’s just there while we get the rest sorted.”

Then two of the boys arrived.

“Happy birthday!” I said to one of them who turned eleven today. “Help us move these smaller chairs to the other room and grab all the big ones to bring in here?”

They set off on their task as a few more students arrived.

“We’re rearranging everything!” One of the first girls explained.

“Why?” A student yawned.

“I don’t know! For a change?”

“Because Ms. Amy was doing it when we came in!”

“But Ms. Amy, it’s so sunny over there! You’re going to fry like a grilled cheese!”

“I liked it better before.”

“Yeah, what about all the other teacher stuff that’s still over there? It’s so far away from your desk now!”

Once everything was moved, and we were mostly satisfied with their placements, we gathered for Morning Meeting.

I explained to the fifth graders that I got the rearranging “itch” from my dad. When I was growing up, he always moved around the furniture in our combined living room/kitchen/dining room. I’d wake up and come out to see things in different places. It would be a bit of a shock to the system, and then I’d get accustomed to it. Ever since, I have constantly rearranged my dorm rooms and apartments to whatever felt right. And I always found that rearranging gave me a refreshed feeling, a sense of starting anew.

I’ve found that with classrooms, even the same one, once you see how the students of that year are using the space, it often becomes clear how best to arrange the furniture. (And it’s apparently good for their brains to have that change!) Sometimes you only need to rearrange once. Sometimes more! (Like last year, which one of our students hated, but Kim loved.)

A half hour later, as we were teaching math, Sol came in and widened her eyes. She walked over to the desk.

“I rearranged!” I said.

“I see that,” she laughed. “Are you trying to slow cook us?” She asked as she shaded her eyes from the sun beaming in through the window.

“Seriously, Ms. Amy,” M said. “Yesterday, this was you: ‘Oh my god, the window is so hot, we need to move things away from the window.’ This is you today: ‘I think I’ll put my desk by the window. Yeah, good idea…’”

He’s not wrong, but I’ll give it a chance. I think it will work.