This October, I decided to get back into rollerblading. Perhaps “get back into” is a generous statement, seeing as aside from the occasional outing as a child and one semester of rollerblading P.E. my junior year in high school, I was never really “into” rollerblading to begin with.

But when I moved to Miami this summer, I had rollerblading on my mind. My friend Arta had lived here in one of our first years out of college, and one of the things she loved about Miami was the ability to do so many outdoor activities like boating and biking and, yes, ‘blading.

So in October when I mentioned this to another friend, Meryl, and was met with equal enthusiasm, we both made a promise to skate together and promptly purchased some stylish 90’s-esque inline skates in bright pastels.

And when the skates arrived, we upheld that promise and went on our first skate date! Meryl picked me up and drove us out to Virginia Key, where we strapped on our new skates and our pads and realized very quickly that we were quite wobbly, the ground was not smooth as we’d imagined, and we both had no clue how to brake, especially when going downhill. So after that outing (which was quite enjoyable truly, filled with long talks and good views and a post-workout smoothie), I put my blades in their new bag, and shoved them in a corner of my closet.

Where they sat for the next three months. Untouched.

I will be honest: all of the joy and enthusiasm for blading that I had felt when I purchased them and put them on, wheeling around my apartment for the first time, dissipated at the early signs of challenge and the very real fears of falling on my butt. I didn’t want to feel that sort of failure again. I was embarrassed, and I was scared. It was easier to make excuses — not enough time, too tired, “oh, I’m trying to get back into running and circuit training actually now” — easier to give up, than to face the fact that if I wanted to improve I’d have to work at it.

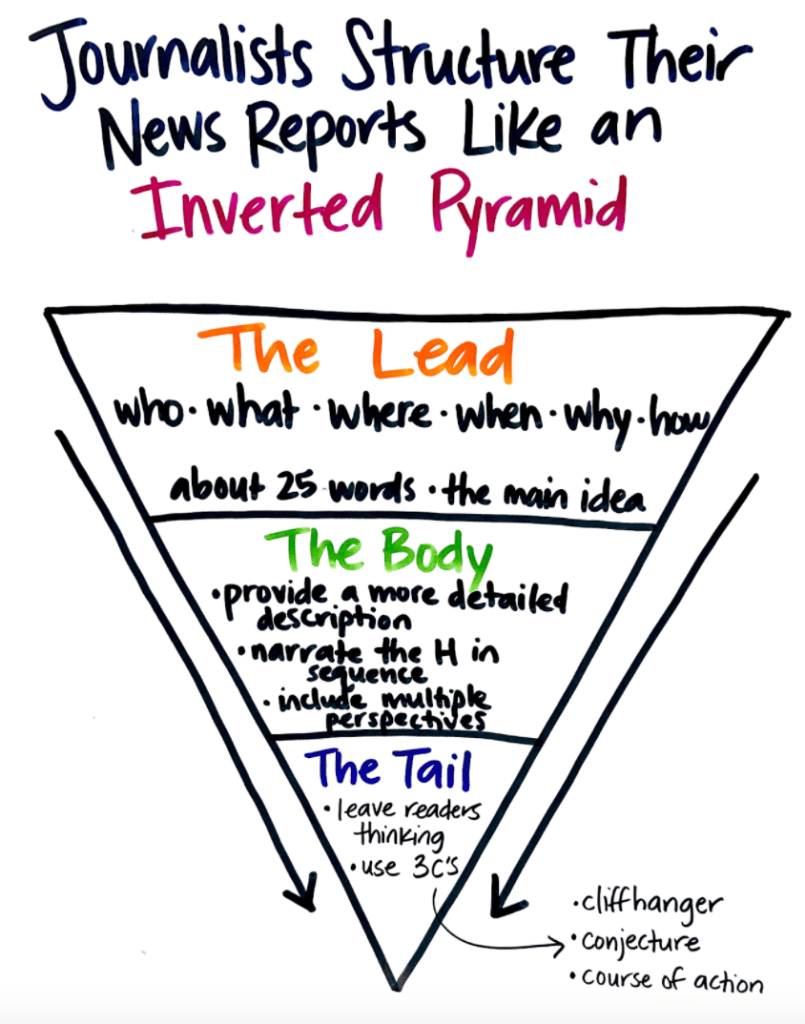

In the education world, there’s something called the Learning Pit.

I’ve taught about the Learning Pit a couple times over the past few years. It comes up at the start of the year usually, when we’re talking about having a growth mindset in the face of challenging academic tasks. I teach my students that it’s important to participate in productive struggle, and how mistakes help you learn because they cause synapses to fire in your brain (Jo Boaler, you are a goddess). We make lists of things someone with a fixed mindset might say (“I can’t do it” or “I’m not a math person”) and things someone with a growth mindset might say (“I’ve got this” or “If I just keep trying, it will get easier”).

But here I was, preacher of all things growth mindset to my students, shoving my rollerblades into the darkest corner of my bedroom closet, letting the dust bunnies slowly devour it until I could no longer tell it was there (except that I could, because the bag was so big).

Then two things happened:

- It was the new year, and you know, we set intentions. After spending winter break in freezing New York, I was determined to take advantage of my new city and go outside more often during the week.

- I got COVID in January and it completely knocked me out, forcing me to take a two-week break from working out.

So I made a choice. I took a long hard look at myself and thought, “You know what, Amy, you’re the one who wanted to start this new hobby. You’re not going to become a rollerblading sensation overnight. And I know that it sucks, but you’ve got to start somewhere. Just put them on and commit to taking them out once a week and practicing. You can only get better from here.”

That first Saturday morning of February, after fully recovering from my run-in with omicron, I strapped up, padded up, and took my blades out for a spin on the Venetian Causeway. It wasn’t perfect. I still couldn’t brake. But you know what? It was fun. It was more fun than I’d had in a long time. I felt… like a kid.

The next Saturday, I bladed again, this time in Margaret Pace Park with the sole intention of practicing using my brakes. I felt silly in my pads and frustrated because it was still so hard, but the views and the music in my AirPods made it worth it.

The following week, Meryl and I woke up early and drove out to the Miami Beach boardwalk where we skated for an hour, laughing and gawking at the views, and then had a delicious brunch of açaí bowls.

Each time I skated, I felt a joy so authentic and innocent that it bubbled out of me. I came home feeling elated.

And then last Saturday, after blading and realizing that while I love to be independent, I was going to need some outside support if I wanted to make significant improvements, I miraculously found a rollerblading group class that was starting in a few days and signed up.

It’s a simple and generous rule of life that whatever you practice, you will improve at.

Elizabeth Gilbert, Big Magic

I’m climbing out of the Learning Pit now. This morning, I woke up early and skated to Dorsey Park to practice the new skills I learned during my Thursday class.

As I head home, I smiled and thought to myself, “I think I’m starting to get this.”

I’m not over the edge yet, but I’ve got the rope in my hands, and I’m enjoying the journey up.