Anyone who knows me knows that I am very organized. (Yes, I do tend to get cluttered. I’m working on it.) I especially value organization when planning Project Based Learning units, which, without some structure, can just seem like a bunch of floating ideas. My three favorite tools for planning PBL units are curriculum calendars, Dr. Gholdy Muhammad’s Culturally and Historically Responsive Literacy (CHRL) framework, and Thinking Maps.

Curriculum Maps

I’d used pacing calendars prior to Samara at my first school for math. Our math coach handed us a stapled pack of pages that outlined which math lessons we should be covering each day of the year in order to teach them all before the NY State tests. That’s not what I mean here when I refer to a curriculum map.

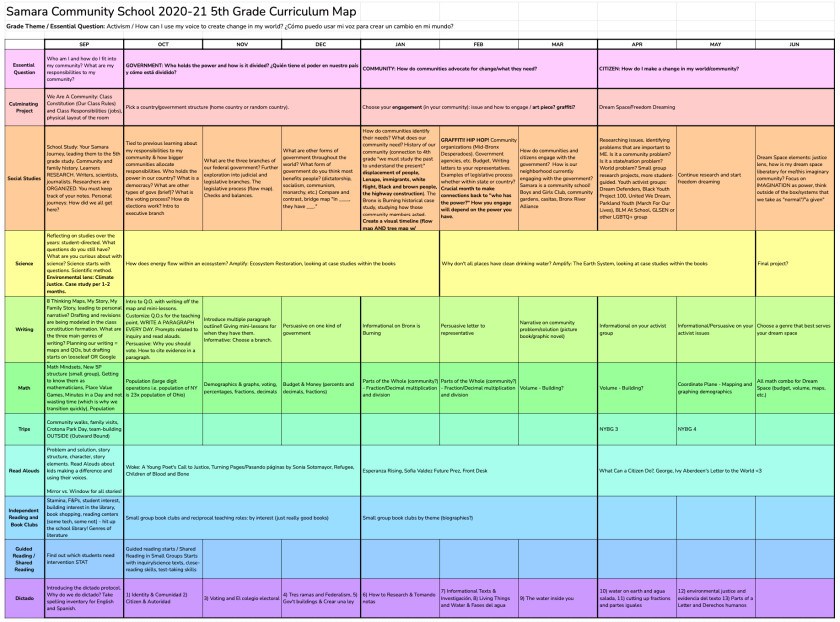

A curriculum map is an at-a-glance overview of your whole year — every month, every subject — so that you can see how all of the pieces of the puzzle fit together. At Samara, where each grade has a theme/essential question, we made sure to include essential questions for our 3 major PBL units, as well as field trips and culminating projects.

Curriculum maps are extremely helpful. Not only can you see EVERYTHING, but you can also easily see how to integrate the various disciplines. For example, in the fall of 2020, our 5th grade PBL unit focused on government and the presidential elections. We saw a window here for teaching multi-digit operations as well as decimal fractions, since we’d be analyzing different infographics with population, demographics, voting percentages, budget, etc.

Culturally and Historically Responsive Literacy

If you’re a teacher and you haven’t heard of Dr. Gholdy Muhammad’s Cultivating Genius, do yourself a favor and buy the book RIGHT NOW. I won’t be able to do it justice in this short blog post. So I’m going to quote from Jennifer Gonzalez and the Cult of Pedagogy, as well as direct you there and to Dr. Muhammad’s website to learn more.

Muhammad believes we’re not reaching many of our students, especially Black students, because our curricula and standards are lacking. The emphasis in our current standards is mainly on skills—skills that can be measured easily on standardized tests—and not a whole lot else…

But there was a time in history when a more complete, more human form of ‘curriculum’ did exist, and it energized and inspired its students—all of them Black men and women—to read, write, speak, and publish with the kind of passion and dedication we would want all of our students to have about learning. This curriculum evolved within the Black literary societies of the 19th century…

These societies were the inspiration for Muhammad’s Historically Responsive Literacy framework, a four-layered pedagogical model that places skills on an equal plane with three other learning pursuits: identity, intellect, and criticality.

Jennifer Gonzalez, Historically Responsive Literacy: A More Complete Education for All Students

Though Cultivating Genius only outlines four learning pursuits, Dr. Muhammad has stated in various workshops and interviews that there is a fifth: joy.

I love using Dr. Muhammad’s framework to guide my PBL planning because it ensures that the unit will connect to students’ lives, teach them the skills and knowledge they need to know in 5th grade, help them to think critically and question “power, equity, anti-racism, and other anti-oppressions,” and provide them with opportunities for joy. It also increases the rigor of any unit. I’ll show you exactly how I use the framework after I talk about Thinking Maps.

Thinking Maps®

In the spring of 2019, I was trained in Thinking Maps, “a set of 8 visual patterns that correlate to specific cognitive processes” (thinkingmaps.com). Unlike regular graphic organizers, of which there are thousands that are usually chosen with no real rhyme or reason (like a sequencing map in the shape of an S for a snake?), there are only eight Thinking Maps. Each Thinking Map is aligned to one specific thinking process: defining, classifying, describing, comparing, sequencing, cause and effect, whole to part relationships, and analogies.

For Samara, a dual language school with ICT classes, Thinking Maps were a no-brainer. And me? I totally drank the Kool-Aid. I still use Thinking Maps all the time in my personal life: for to do lists, grocery lists, packing lists, even when Alberto and I were planning our move to Miami! They are unbelievably useful, and honestly, they just make sense.

The way I use Thinking Maps for planning PBL units is as follows:

- Brainstorm with a circle map. Get down ALL of the ideas I have. Ideally do this with a thought partner.

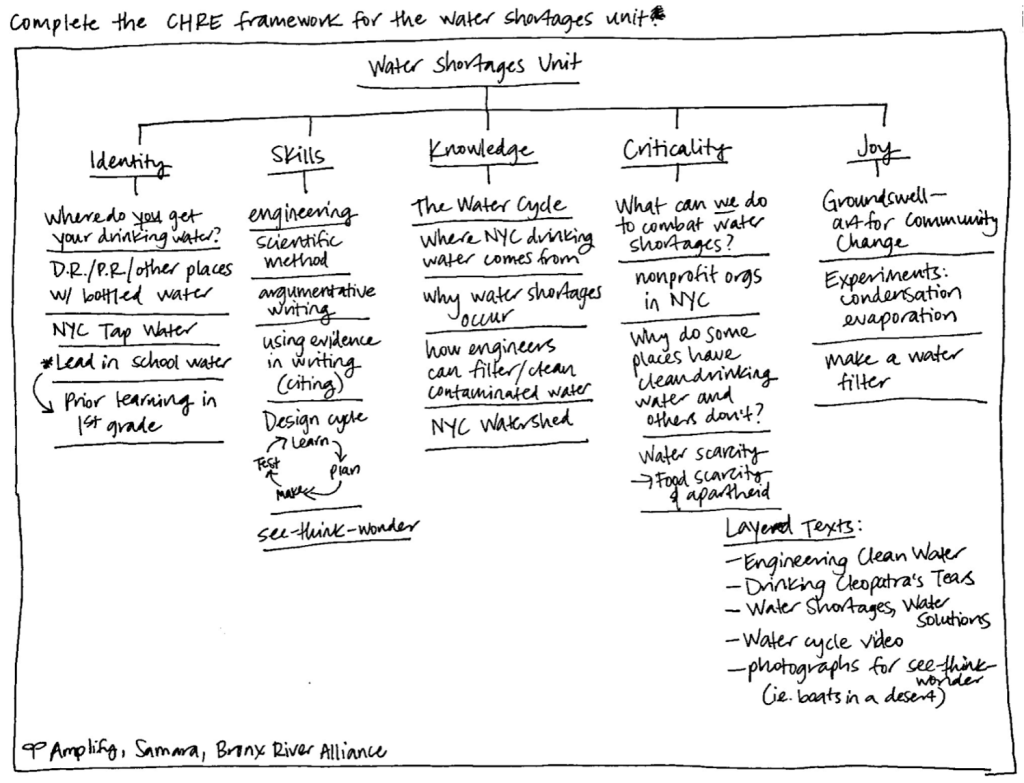

- Categorize all of the ideas according to Dr. Gholdy Muhammad’s CHRL framework.

- Backwards plan and sequence the unit: What needs to be taught first so that students arrive to the final project?

I can then input the sequence into my curriculum map and work on holding myself accountable as well as staying flexible for student choice and voice.

Putting it into Practice: Our Current Unit of Study

In December, I roped Josue, our tech teacher, into brainstorming for our ecosystems unit with me. We created a circle map that overflowed onto a second page.

Over winter break, holed up in NYC at my parents’ house during the omicron wave, I researched resources and field trips, adding to the map and bothering Josue with my constant texts. On the plane back to Miami, I organized the ideas into a tree map with the CHRL framework.

I revised and reworded the essential question until I finally got it right: How can we encourage our KLA community to take a more active role in caring for South Florida’s ecosystems?

Then I paced it out: How would I launch the unit with the students so that they could come to this question on their own? When would the field trips make the most sense? What would students need to learn about and build expertise in before starting to take action? How could I align math, reader’s workshop, and writer’s workshop units so that they supported the flow of the project?

Into the curriculum map the ideas went:

January – launch and start initial research on ecosystems; start informational writing unit

February – deeper investigation into ecosystems, including virtual and in-person field trips to the mangroves of Key Biscayne and the Everglades; final informational writing bend = quick-write brochure about the Everglades habitats and endangered species

March – begin conversations about taking action, interview eco-artists, urban designers, nonprofit employees, etc; start opinion writing unit

Since January, the unit has taken on a life of its own. The students really grabbed onto mangroves more than any other ecosystem. A request for an interview with eco-artist Xavier Cortada led to us participating in his Plan(T) project school-wide, bringing mangrove propagules to KLA. An interview with Anna, our atelierista, sparked criticality and gave seed to a community urban design culminating project that integrates math and art, which we’ll launch after spring break.

But having that organizational plan? It’s like a road map. You may end up taking an alternate route, but having the map in front of you helps you keep the final destination in mind.

Leave a comment