When my husband and I decided to move to Miami, I was sure about one thing: whichever school I taught at would need to embrace inquiry, integrated studies, and project based learning. I was lucky to find KLA, which has allowed me the same creative freedom that Samara did in designing curriculum that is meaningful and relevant for my students.

The way I approach project based learning is heavily influenced by my time at Samara and the professional development I received while teaching there, as well as by what I’m seeing and learning at KLA with its Reggio-inspired model.

A disclaimer: I am in no way an expert on project based learning. I do, however, think I have a knack for it. Planning projects is fun (if you’ve ever planned one with me, you know how excited I can get), and it’s probably the only part of planning that never truly feels like work, because I am learning so much in the process.

I know that I’ve learned the most about effective teaching through other teachers—talking to them, observing them, reading their blogs/social media. So my goal is to document and reflect on my planning process here in bite-sized blog posts, in case it helps anyone out there.

What is Project Based Learning?

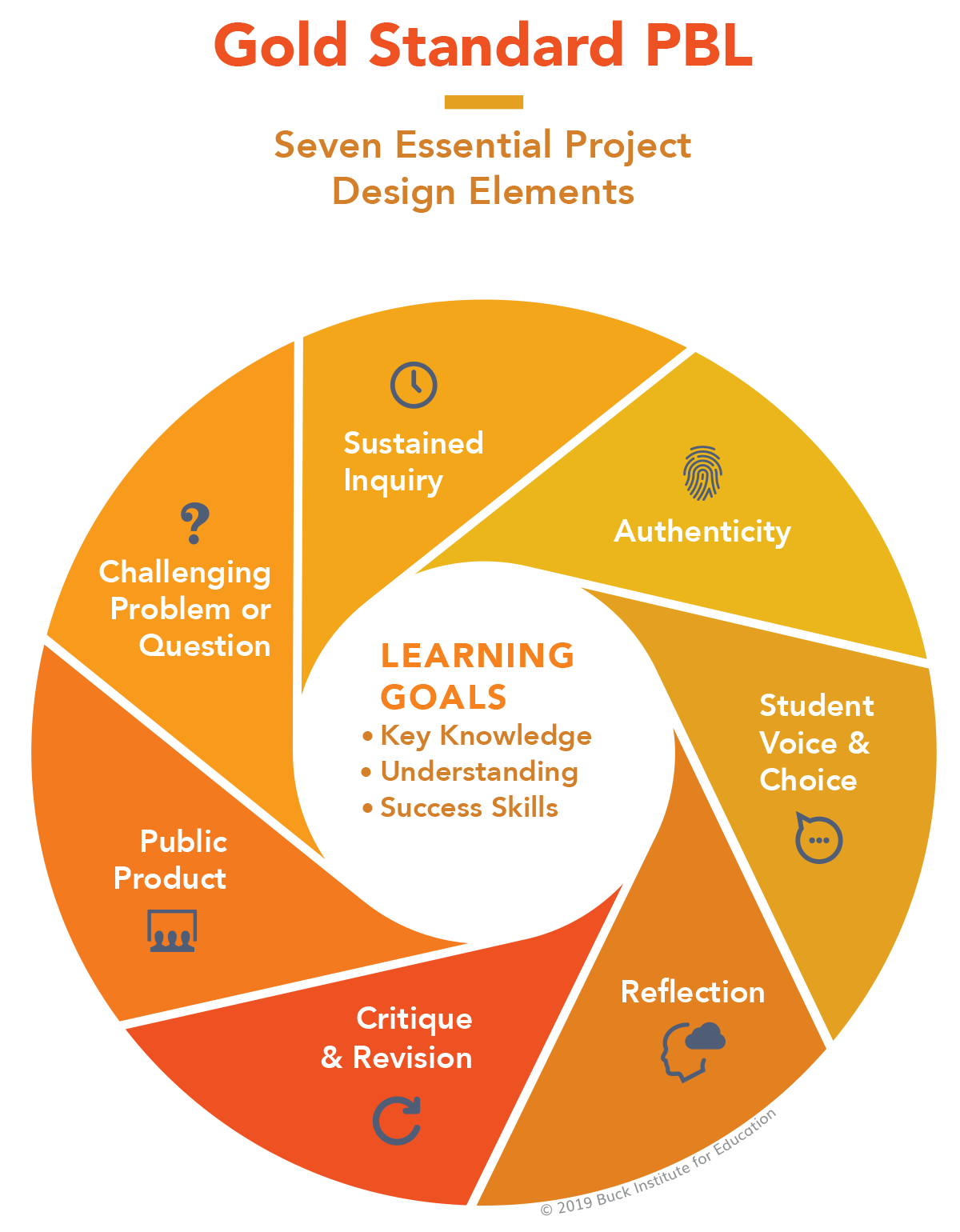

Before I launch into this blog series, it’s important that we ground ourselves in a definition for project based learning. PBLWorks, the leading provider of professional development for project based learning, defines project based learning as “a teaching method in which students learn by actively engaging in real-world and personally meaningful projects” (pblworks.org). That said, project based learning (PBL) is NOT simply “doing projects.” I particularly like this explanation from their website:

“We find it helpful to distinguish a ‘dessert project’ – a short, intellectually-light project served up after the teacher covers the content of a unit in the usual way – from a ‘main course’ project, in which the project is the unit. In Project Based Learning, the project is the vehicle for teaching the important knowledge and skills student need to learn. The project contains and frames curriculum and instruction.”

PBLWorks

I was lucky enough to receive a full day of professional development from PBLWorks before leaving Samara, and I still have a lot to learn from them, particularly in terms of assessment and student reflection, critique, and revision. I already know these are my next steps as I look toward planning future PBL units. Onward.

Depth Over Breadth

One of the first things I learned at Samara about PBL is the idea of valuing depth over breadth; when you decide to do thematic units or projects, you simply have to give up the idea of being able to teach everything.

This can be a tricky concept to swallow.

But I have to teach all the things!

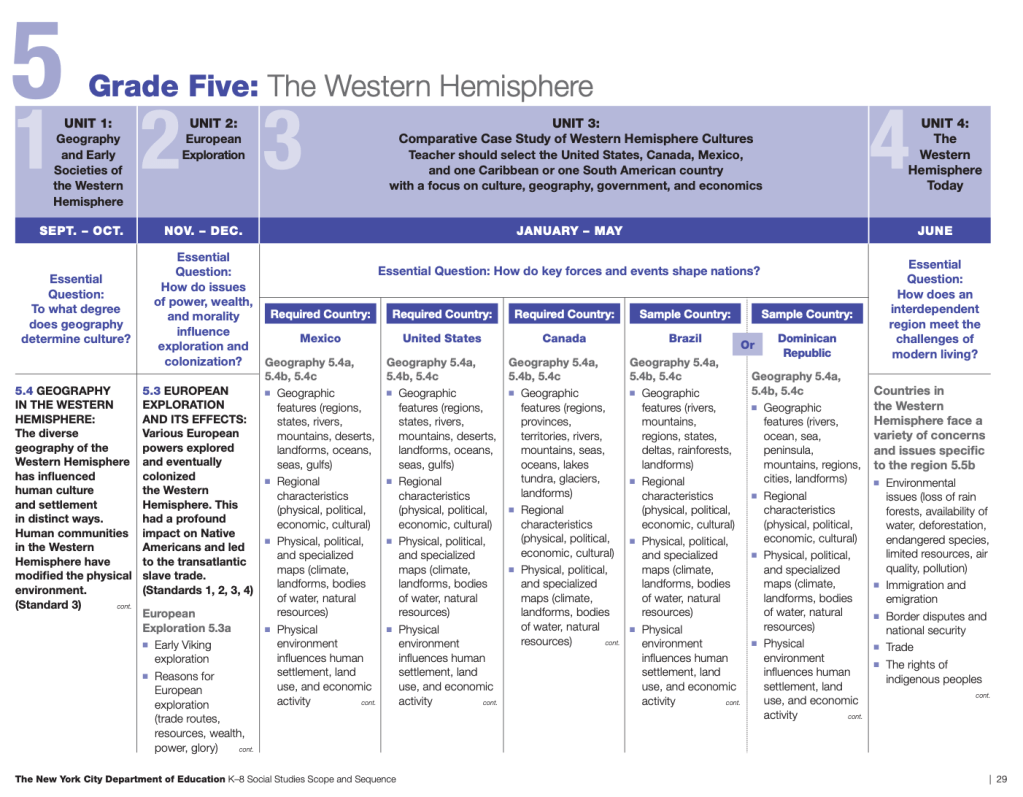

Take a look at any social studies or science scope and sequence and you’ll see what I mean. There is so much that states and cities and districts want you to teach in a single year for a single subject that it can be overwhelming, if not downright impossible. The teachers who do try to cover it all usually end up sacrificing depth in favor of breadth—students get a little sprinkling of everything, but don’t get a chance to linger and build their expertise. Not very effective.

With PBL, we want students to think critically, problem solve, collaborate, and communicate their newfound understanding in meaningful ways. This means we need to go deep.

Where to Begin

I like to begin by looking at the standards and the scope and sequence. NYC has a beautifully designed, easy to understand social studies scope and sequence. Florida? Not so much. Either way, get familiar with what your state wants students in your grade to learn. Focus on science and social studies, as these are the subject areas that often get “sprinkled” throughout the school day/year, pushed aside in favor of literacy and math, which are absolutely necessary in the primary grades.

Once you’ve gotten an idea of the standards, look inward:

What do you see in the scope and sequence that you are passionate about?

If you’re passionate about something, it will be contagious — others will get excited about it because you are.

Next, look at your students:

What do you see in the scope and sequence that they are or might be passionate about?

Get to know your kids really, really, really well. What questions have they already asked that connect to these topics? What are their interests, their passions, their strengths?

Finally, look at your community:

What issues in your neighborhood/town/city relate to the topics you and your students are passionate about?

I’ve found that project based learning is most effective and meaningful when it’s place-based too. What resources exist in your community to bring this learning to life?

Starting with a Seed

Here’s how I followed this for our current unit of study.

- What do I see in the scope and sequence that I’m passionate about?

I am passionate about the environment and combatting the effects of climate change. I see this in the Florida State Standards SC.5.L.17 about Interdependence.

- What do I see in the scope and sequence that my students are passionate about?

Many of my students love animals and wildlife. Some of them who moved here from another state have asked why our school doesn’t recycle. Most of them love being outside and are very active.

- What issues in my neighborhood/town/city relate to the topics we are passionate about?

Miami is a city built on top of what was once part of the Everglades. Climate change is impacting Miami immensely because of sea level rise. Lots of flooding issues. There are many organizations working to combat pollution of Miami’s beaches. However, there’s a lack of easy/cheap recycling, and hardly any composting.

I had the seed of an idea for the unit. Now I just needed to start planning for it. To be continued.

Leave a comment